TRAINING STORIES: Fun and heroic tales from former Knicks assistant and Nets head trainer Timmy Walsh

A doctor at a Los Angeles hospital had just cleared one of the Nets players to travel with the team, but Timmy Walsh knew something wasn't right.

Call it a trainer's intuition — built on over three decades of experience.

"I saw what I saw," Walsh said. "I'm not taking him on a plane."

What Walsh witnessed earlier that night was Mirza Teletovic, a forward with Brooklyn, struggling to breathe during a game and pleading for help. By the time they reached the hospital, Teletovic had calmed and the symptoms subsided.

But Walsh wasn't satisfied with the non-diagnosis.

"My gut told me he's not OK," Walsh said. "I know the ER doctor is saying he's OK, but something's not right. So I said, 'If they don't want to do a CT, I'm going somewhere else to get one.'"

Walsh's persistence resulted in that CT scan, which uncovered multiple blood clots in Teletovic's lungs. Under those conditions, a plane ride to the next game could've hastened a pulmonary embolism. Instead, Teletovic was administered blood thinners, the clots dissolved, and he's currently enjoying his sixth season in the NBA.

"He could have gotten on the plane and he could have actually died," former Nets coach Lionel Hollins said.

It wasn't the first time Walsh potentially saved a life during his 32 years as an NBA trainer. It wasn't the last time, either, before he was unceremoniously dumped by Nets GM Sean Marks prior to the 2016-17 season. But the Teletovic story underscored the characteristics that defined Walsh as a trainer — alert, engaged and, above all else, trusted by his players.

"More than anything, I think this job is more about the personality and the person who you are. And it's who I am," Walsh, 55, said. "I've spent my whole adult life helping people and giving and I'm fine with it. And I loved it."

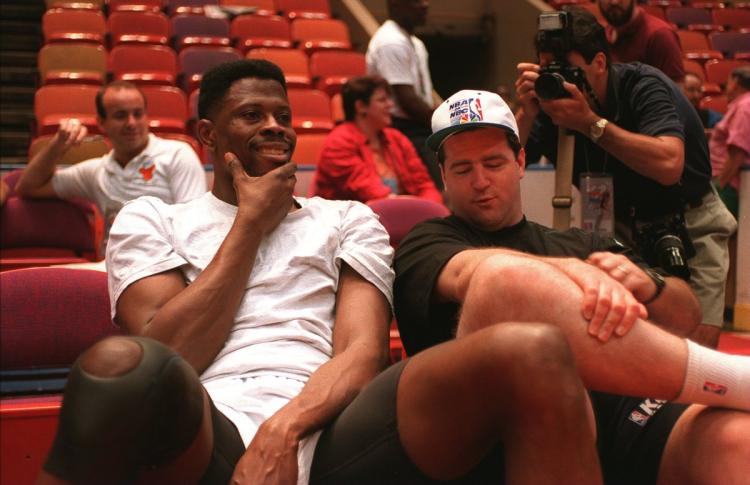

Tim Walsh shared special relationship with Patrick Ewing that included assisting in Knick center’s eccentricities about germs. (GETTY IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES)

Much of Walsh's attention to detail was originally forged by his relationship with Patrick Ewing and the center's high-maintenance superstitions.

Separated by only about two months in age and sharing the same middle name (Aloysius), there was plenty of common ground for Walsh, the former baseball player from Newark, and Ewing, a 7-foot Jamaican. Their connection lasted for 13 years together with the Knicks.

"He was just down to earth," Ewing said. "We just clicked. He and I just clicked.

"Plus, he was really good at what he did."

Walsh was an assistant in New York to long-time head trainer Mike Saunders, becoming the first fulltime staff member with that title on any NBA team. Ewing was drafted a year later, ushering in the franchise's second (and last) golden era.

While Ewing played like a bowling ball in the paint, he was a germaphobe behind the scenes who desired order. Ewing only trusted Walsh with certain tasks.

"He had to be the one to carry my shoes," Ewing said. "He was the only person who was allowed to touch it."

But it wasn't just the sneakers. There was a specific wooden coat hanger Ewing required in his locker — "God forbid I lost it or it wasn't there, he thought he'd have a bad game," Walsh said — along with certain ice bags and Ace bandages for his knees.

Ewing's cups of water on the bench had to be freshly-poured, rather than sitting on a tray collecting germs.

"He was very aware of people who didn't wash their hands," Walsh said. "Patrick knew from two rooms away if someone went to the bathroom and didn't wash their hands. He knew it. And Patrick was not touching that person all night. Two hours later, in the middle of the game, if that guy just hit the game-winning shot, he was fist-bumping him instead of shaking his hand. He wasn't touching the guy."

Tim Walsh (far r.) served as head trainer for Nets for decade and a half, where one of his tasks was keeping Vince Carter on floor during important moments in mid-2000s. (HOWARD SIMMONS/NEW YORK DAILY NEWS)

Eventually, Ewing and Walsh grew so comfortable together that words were no longer necessary. When Ewing touched his nose on the bench, he needed a tissue ("He'd sweat so much he just felt he needed it," Walsh said). When he held up two fingers, it meant ice.

"You know in baseball, you have all these different sign languages. We had our own signs for different things," Ewing said. "We just developed our own way of communicating."

In 1997, Walsh graduated to head trainer with the Orlando Magic. He returned home to accept the same position with the New Jersey Nets in 2000, one year before Jason Kidd's arrival and the start of the greatest era in the franchise’s NBA history.

Along the way, Walsh learned how to adjust his methods and advice based on a player's personality. With Gerald Wallace, for instance, there could be no reasoning.

"Gerald Wallace drove me nuts," Walsh said of the former Nets forward. "This guy had stuff where he shouldn't be playing. He just banged his knee, he can't walk. He's going to come in and I'm going to have to tell him he's not playing and I know he's going to want to argue with me. He's going to tackle me, he's going to want to kick my ass. But with him, I would just hide his uniform. I would get the uniform and put it away. He would walk in and it wouldn't be in his locker.

"And after the game, he's like, 'You're right, I couldn't have played.'"

Vince Carter required a more nuanced approach. During his first season with the Nets in 2004-05, the future Hall of Famer was dealing with Achilles bursitis and frequently in pain.

With New Jersey needing a victory in the final game to get into the playoffs, Carter was kicked in the heel in the first quarter at Boston and stormed off the court. Walsh quickly followed Carter, shooed away the trailing doctors and stopped the player before he got inside the locker room.

"I said, 'No we're not going in there,'" Walsh recalled. "I said, 'Vince, if we go in there, you're going to cut the tape off and put ice on it and you're done.'

"I said, 'Right now is when heroes are made. We're going to go out there and take a minute, let this thing calm down.'"

No task was too small for Tim Walsh. (BILL KOSTROUN/ASSOCIATED PRESS)

Walsh convinced Carter to run through the hallway until he felt comfortable. Carter returned to play 44 minutes and score 37 points in the Nets' victory.

"Timmy was very good psychologically with guys," former Nets president Rod Thorn said. "Probably five or six or seven times during the course of the year, (Carter) got some sort of injury and he would go off the court like he was about two minutes from expiring. And Timmy would go back and work with him and he would come back and play great.

"I think a big part of training is understanding your players and how you deal with different players. And Timmy was very, very good at that because he got to know the players and he knew how to make them tick and what you need to do in order get them to perform to their best capabilities."

Getting to know players went beyond their injuries, treatments and equipment preferences. A trainer's job in the 1990s also meant he'd have to retrieve spare pants — as Walsh did after Pat Riley's were ripped during a brawl against Phoenix — or retrieving a backup jersey when a uniform was torn. "We were always preparing for that," Walsh said.

And for all traumatic occasions. "There always was the sense you were the priest, the rabbi, the bartender and psychologist."

Sometimes that involved covering up an innocent mistake, like when Courtney Lee, formerly with the Nets, went to the wrong arena for a home game.

"(Lee) calls me and says, 'I'm at MSG. There's nobody here,'" Walsh recalled. "I say, 'That's because the game is at the Izod Center.'"

Although Lee arrived late after commuting back through the Lincoln Tunnel, he still made the pregame team meeting and nobody knew about the snafu. Walsh had hidden his jersey in the X-ray room so it would be assumed Lee changed and was warming up, rather than fighting rush hour traffic

"I would never lie for a guy," Walsh said. "If the coach asks me directly, I'm not going to lie. But you take care of these guys. Then they take care of you and appreciate it."

Tim Walsh does everything possible to keep Nets star Vince Carter on the court. (KEN GOLDFIELD FOR NEW YORK DAILY NEWS)

Other times, Walsh was more of a therapist — or a consoling friend. While a trainer for the U.S. national team in 2003, Walsh happened to walk in on Karl Malone sobbing near his hotel room. For the next eight hours, Walsh helped Malone deal with the death of his mother due to a massive heart attack.

She was just 64.

"He literally just found out," Walsh said. "So now I'm like, 'Okay, this man needs me here.'"

Counting the Teletovic diagnosis in L.A., Walsh potentially saved three lives in a span of less than two years. The most well-known instance was reviving assistant coach Jim Sann on the practice court following a heart attack.

That story had only previously been told from Sann's perspective, about how he collapsed on the practice court and, "was on my way out." Walsh said he was actually in another room when a colleague rushed over with the news.

"I run out, sure enough he's lying there, face-down," Walsh said. "He's breathing but he's struggling, (gasping for) breath, like right before he's going to stop breathing.

"So I turn him over, he has a cut on his forehead and he just stops breathing."

Walsh then performed CPR and shocked Sann with a defibrillator. Nearly three years later, and now with a stent in his heart, Sann is still an assistant coach with the Raptors.

For the sake of privacy, Walsh didn't want to reveal the identity of the third beneficiary of his life-saving work, only that it involved a player "in bad, bad shape" lying next to his bed in the hotel room. Still, the story was known throughout the NBA community and Walsh was honored as the league's Athletic Trainer of the Year for consecutive seasons.

"Everything's always worked out and I knew what to do. I've trained for this. I've always, in my mind, say. 'Be the calmest person in the room and do what you have to do.'"

About a year after receiving his second straight award as the best trainer in the NBA — and third overall — Walsh was unemployed.

After 16 years with the Nets — becoming the longest-tenured person remaining on the basketball staff — Walsh said he didn't get much of an explanation from the new GM about why his contract wasn't renewed.

Marks, according to Walsh, said he was going with a different skillset at trainer, without elaboration.

"Was I angry? I had my moments. I do. I thought, and still think, and know, that I gave everything I had to the organization," Walsh said. "But I had to respect the fact that my contract was up and they wanted somebody else."

Marks promoted Walsh's former assistant, Lloyd Beckett, to head trainer. But more important to the hierarchy, Marks hired a former member of the Navy SEALS, Zach Weatherford, to be the head of the performance team. The organization's emphasis was placed on rest, to the point that Marks was singled out by former commissioner David Stern for taking that trend too far.

While bothered by the way it ended, Walsh said he's neither bitter nor anxious. He turned down a few opportunities with college programs and resurfaced in his field at Sportscare Physical Therapy, where he is the vice president of Sports Medicine. The CEO of the business, Ron Lombardi, sold the position to Walsh as more conducive to the trainer's family life. Walsh has enjoyed that benefit.

"For a stretch there, I wasn't home for Thanksgiving for 12 straight years," Walsh said. "My son's first 11 years of his life I never spent Thanksgiving with him."

Still, Walsh isn't ruling out a return to the NBA. He's not looking, but he'll listen. Even if he never returns, Walsh will always have three NBA Finals, and the gratitude for the lives he saved.

For the official story link go to http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/basketball/fun-heroic-tales-ex-knicks-nets-trainer-timmy-walsh-article-1.3672675